Most of the time, Sheldon Deluty wears hospital scrubs. For 11 months out of the year he’s an anesthesiologist at New York University’s School of Medicine. For one week out of that other month, however, Dr. Deluty bundles up in layers from head to toe and, after traveling to a remote location beyond the Arctic Circle, spends his time photographing the aurora borealis—the light show courtesy of the magnetosphere known as the Northern Lights. Believe it or not, he thinks about photography the same way he thinks about anesthesiology: it’s based in science but the nuance is the art.

“I’ve spent the last 32 years giving anesthesia, training residents and taking care of patients,” Deluty says, “working in rooms that have no windows, utterly divorced from the natural world, in a very high pressure, intense and demanding environment. Anesthesia is a very science driven business. You have to know pharmacology and physiology, but most days, along with the basic underlying scientific principles there’s a great deal of art to the science. You develop feels for drugs, a feel for critical situations, you read your environment. I tell the residents it’s really no different than driving. When you’re driving and you see a stop sign do you slam on the brake? Of course you don’t. How do you know how to slow your car to get to a stop? That’s the art to the science. The world is analog, it’s not digital, it’s not all or none. What drew me to photographing the aurora is the technical challenge and the huge amount of art and judgment applied to the way you do it.”

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 15-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600

The Best Place For Auroras On Earth

Over the course of the last decade, Deluty has spent much of his limited free time learning all about the aurora—what causes it and how best to photograph it. The most important factor, he says, is finding the perfect place to view them. It all starts with the location, and while there are many places where seeing the aurora is possible, there’s one place on the planet that seems purpose built for it. The variables of landscape and climate come together to make it Deluty’s end-all, be-all location for photographing the aurora. It’s a little city in Northern Norway, a few hundred miles above the Arctic Circle, called Tromsø.

“You would think that somewhere up there is barren hell,” Deluty says, “except that it’s a university town of 10,000 students and a major hospital medical center. It’s like the capital of northern Norway. And what makes Tromsø unusual is even though it’s north of the Arctic Circle, it sits on the Atlantic coast and because of the Gulf Stream the winters are very mild. So that in Tromsø itself during the wintertime, unless it’s a bad blizzard, the temperature is usually about 30 or 35 degrees. If you went inland from there you’d be in the middle of Siberia and it would be 40 or 50 below zero.”

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 20-sec., f/2.8, ISO 800

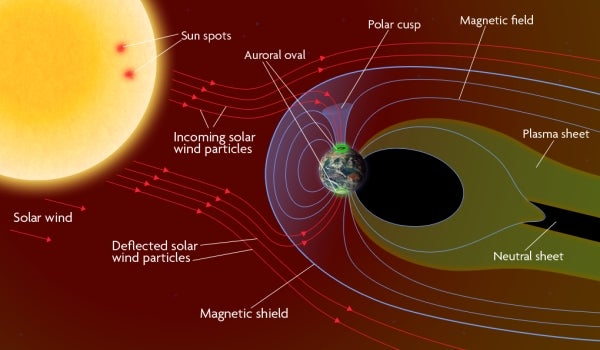

Astronomically, Tromsø sits under the Auroral oval of the magnetosphere of our planet. It’s right under where the high-energy radiation comes into the earth’s atmosphere from the magnetosphere. If there’s auroral activity, people in Tromsø see it. It fills the sky from horizon to horizon and lasts for hours. And because of its location and terrain, with mountains slightly inland and the Atlantic Ocean on the western side, Tromsø has microclimates that make it easy to find clear skies and good views, and the temperate weather to comfortably stay out as long as the light show continues.

“You can have snow in one place in the area and drive 30 or 40 miles and have a clear sky,” Deluty says. “So at night the tour guides (I travel with Arctic Guide Service Tromso, Norway) will go to five or six different places over maybe 100 miles in different directions chasing a clear sky. Because if there is a clear sky between 9 and midnight, inevitably you’ll see the aurora. In the three weeks that I’ve been there, out of the 18 nights I could have gone out to see the aurora, I went on 14 or 15 of them and saw the aurora every night in some capacity. Two or three of the nights people lie down in the snow and just stare at the sky! Four or five of nights were pretty good, and one or two of them were not that impressive. But the point is I saw it every night in many different places in the area and I got to see it manifesting in many different ways in the sky.”

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 25-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600

Aurora Shooting Techniques & Gear

Because of his intensive study, Deluty has refined his techniques for photographing the ethereal subject as well. It starts with a fast lens and a fast shutter speed.

“I have an f/2.8 lens,” he says, “and what I play around with is the shutter speed and the ISO. I’m constantly modifying the two looking for a way to capture it as fast as I can. The aurora usually looks like a smear in still photographs because when you shoot with a lens that doesn’t have a fast aperture and you don’t have the ability to boost your ISO or you don’t know what you’re doing, you end up shooting long exposures. That’s what the books say to do—shoot with a shutter speed of 15 to 30 seconds. The aurora actually moves, so what you’re trying to do is freeze it. If you freeze it too fast you don’t get enough detail, if you let it go too slow you get a smear. It’s a balancing act”

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 25-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600

The foundation of Deluty’s approach is his treasured Sony α99 DSLR. He uses it in manual mode and starts with a shutter speed as fast as four or five seconds, but seldom longer than 15 seconds, enabled by a lens with a fast f/2.8 maximum aperture and a sensor capable of low noise and high dynamic range at high ISOs. Though he does try to limit his ISO to 800 or 1600, only going to 3200 in the rare instance it’s required.

“If you look at every article,” Deluty says, “most people will tell you to start the other way: get a lens with f/2.8 if you can. Assuming that you can get your hands on an f/2.8 lens, recognizing that those are expensive, the next thing they talk about is what ISO you can shoot at. And here I have a lot of bones to pick with a lot of the stuff on the web, because they recommend ISO 3200 and 6400. They also say try to avoid going to the arctic during the full moon. In 2015 I was there during a full moon, because I couldn’t avoid it, it’s when I could get off from work. The moon was the most amazing help. I was shooting at night under a full moon at an ISO of 400 at a shutter speed of 4 or 5 seconds. If that’s not going to capture the aurora at a good display I don’t know what is. If the moon is at your back you end up getting daylight illumination where it lights up the snow.”

“Ideally you want to shoot the fastest shutter speed you can,” he continues. “The problem is, for most cameras that comes with the cost of a very high ISO. For a lot of people ISO 3200 is where they end up shooting. And then of course you get noise.”

To support the camera, Deluty uses a Feisol Carbon Fiber Tripod (model CT-3441) with the CB-40D ballhead. "It's incredibly light weight, yet sturdy enough to hold the substantial combined weight of my α99 and my 16-35mm f/2.8 Sony-Zeiss lens in the windy environment of the arctic. These are important considerations where constant travel and necessity for camera lens steadiness during long exposures is of paramount importance."

Dealing with noise in post-processing is a big part of Deluty’s success with aurora. To handle the heavy lifting he relies on DxO’s OpticsPro software.

“The program has an algorithm that works specifically on RAW pictures, called PRIME (an acronym for Probabilistic Raw Image Enhancement) noise reduction technology,” Deluty says. “On my computer which is pretty fast, it takes DxO four minutes to process a 24MP raw image file.. It literally goes pixel by pixel through the image. And what you see in the after photographs is the stars come out of the sky. They appear. You’ll also see lens distortion disappear. When you run pictures through OpticsPro the first thing it does is identify the camera body and lens, and it has a database of virtually every camera and lens on the market because DxO also does lens testing, and it immediately applies the optics correction for pin cushioning or barrel distortion. So the picture bends first, then you start playing around with the noise reduction, and in some pictures it’s absolutely magical. You can’t create what isn’t there, but it pulls things out. You get incredible noise reduction.”

Back on location in the Tromsø night, Deluty has his camera set to ISO 800, his lens at f/2.8 and his shutter speed is typically between 8 and 12 seconds.

“Beyond 30 seconds you start to see star trails,” he says. “I’ve never shot longer than 30 seconds. If you need 30 seconds you’d better just pack it in because you’re just going to get a smear. You’re not going to get anything. “

“And of course the other problem is,” Deluty adds, “every time you shoot a long shutter speed the camera spends an equal amount of time processing the image. My Sony α99 makes an equivalent black image in the camera and subtracts all the black out of it to produce the image. Interestingly, I’ve learned one of the reasons my battery lasts well in 10 or 20 degree weather is that the processing at 15 to 30 seconds makes the body of the camera very warm and the battery actually lasts as long as it would if I was shooting in a warmer climate. And I love the α99’s GPS, which is a godsend because it tells me exactly which fjord I’m on. And then of course there’s the thing with the screen, which articulates out at 90 degrees which allows me to angle my camera up on a tripod and I trigger the shutter with a remote.”

The details may seem incidental, but the a99’s articulating screen and remote control mean the difference between working in comfort and crawling around in the snow in the middle of the night. Comfort is an important consideration when it comes to maximizing your time photographing aurora. That’s part of the reason Deluty returns to Tromsø time and again. For an arctic city it’s really pretty warm.

“I’m standing some nights in a sweater,” he says. “I take my jacket off. I’ll go out layered with a sweater, with my gloves, with carbon hand warmers in my pocket, and I’ll work out there with a sweater and a hat on and I can work very comfortably that way for 30 or 40 minutes. It’s a very civil environment to work in considering how far north it is. That’s one of the magical things about Tromsø. And for compositions, there’s ocean, there are fjords, there are lots of things.”

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 20-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600

Aurora Forecasting

Your odds of finding an aurora to photograph are greatly enhanced by tow things: Where you are and the Internet. "There are a multitude of websites and apps that are measuring the solar activity across the planet," Deluty explains. "You can go look at them and they give you a number on the Kp index from 0 to 9. If it’s 9, which it almost never is, there’s been a coronal mass ejection and just about everyone could see the aurora. That’s when you get the reds, purples and blues. More often than not in Tromsø, you have a good shot at a 4 or a 5, maybe a 6. I probably had a 7 one night where I could see and photograph reds in the aurora. More often, it’s about 3 to 4, which in most places isn’t bright enough to see. But in Tromsø under the oval, if the sky is clear or even partly cloudy, you’ll see it. It’s all about location, location, location."

Other Aurora Hot Spots

There are other locations Deluty has visited in order to photograph the aurora, each with varying levels of success. One place in particular tops the list of destinations he’d like to visit to photograph aurora.

“In Yellowknife,” he says, “in the Northwest territories of Canada, you’re 250 miles below the arctic circle, inland on a flat area averaging 240 nights a year of clear sky. It’s a wonderful place to view the aurora, it sits under the auroral oval even though it’s lower down on the planet because the oval is on a rotated sphere. But at night there the temperature drops to 30 or 35 below zero, and with the wind it’s 50 below. Yes, you can stand outside when you’re well geared up, but taking pictures is an incredibly difficult nightmare. Batteries don’t last, you keep running in and out of the cabin, condensation sets in, it is a very difficult place to photograph the aurora. And in Yellowknife it peaks after midnight, like 2 to 3am. In Tromsø it tends to peak between 9pm and midnight. After midnight it seems to go away, and nobody really knows why.”

“In my mind,” Deluty says, “Iceland is the dream place. The terrain there is so otherworldly. To shoot the aurora there would be the Holy Grail for me. But I don’t have the time or the resources to spend a month in Iceland, which is what you have to do to give yourself the odds to see it. A week is not going to do it. The problem I’ve had with Iceland is the weather. I’ve been there in the summertime. It’s a beautiful place to photograph because of the terrain, but the weather has been awful. In Reykjavik it rains almost all the time. And if it’s raining or overcast on the island, there’s nowhere to go where the weather is clear, you’re just socked in.”

“Over the course of several years of research,” Deluty says, “I’ve learned about the tripods and the remotes and the gear to dress in, but more than anything else I’ve learned some of the art to the science of taking pictures of the aurora. And having several nights a week to go out and do it for several hours at a time, I’ve had a blast playing with it. And I’m going to keep doing it. I like it. I’ve come to understand what draws me to it is what draws me to what I do for a living: the art to the science, the challenge to get that picture.”

What Is The Aurora?

"I like being out on the tundra standing there. It makes me feel alive in a way I cannot put into words. And from a teleological or other standpoint, if I take a step back, the aurora is the reason that actually life is on this planet. Because if there was no magnetosphere to capture the solar wind, we’d all be dead of radiation. So the aurora is the radiation that makes it through the magnetosphere and is collected at the poles that drops down into the atmosphere that ionizes oxygen and nitrogen. I know on the quantum mechanics level what it does: it changes the orbital configuration of electrons, they release the energy in the form of visible light. You are literally watching the life-sustaining process of the magnetic shield of the earth. That’s what the aurora is. But it happens to be beautiful whether or not you know a damn thing about physics or chemistry."

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 6-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1000

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 15-sec., f/2.8, ISO 800

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 10-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600

Sony α99, Vario-Sonnar T* 16–35 mm F2.8 ZA SSM II lens. 8-sec., f/2.8, ISO 1600